SHŌGUN (2024) – Miniseries

When a mysterious European ship is found marooned in a nearby fishing village, Lord Yoshii Toranaga discovers secrets that could tip the scales of power and devastate his enemies.

When a mysterious European ship is found marooned in a nearby fishing village, Lord Yoshii Toranaga discovers secrets that could tip the scales of power and devastate his enemies.

This meticulous adaptation of James Clavell’s 1975 novel Shōgun is a masterclass in modern storytelling, engrossing from the opening few seconds of the first episode. A ship, the Erasmus, looms out of the thickest sea fog, its sails in tatters. On board, the bedraggled and filthy pilot, John Blackthorne (Cosmo Jarvis), tries to convince his captain that they’ll soon make landfall. With no food or water left on board, the captain demands the pilot’s pistol. We hear the shot as Blackthorne returns to the darkened decks. This rather austere opener will have later resonance when others choose the manner of their own deaths. Yes, Shōgun is bleak and brutal, but so beautiful and romantic that it swiftly becomes immersive, making it almost impossible to tear one’s eyes away from the screen for the ensuing ten hours, even when some of what we’re seeing may be difficult to watch.

I’m sure most readers interested enough to read this review will already have binged the entire series. If you haven’t and enjoy period dramas of any kind, I recommend you get started. It will also appeal to lovers of fantasy epics—which it certainly isn’t—as it serves up a story of an outsider entering a completely alien realm that’s just as otherworldly as any found in classic portal stories, but also far more real.

It’s 1600, and the Erasmus, a privateer ship, searches for a safe route to the islands of Japan. This route is a closely guarded secret by the Portuguese, who have monopolised trade in Japan’s silks and precious metal artefacts. When the ship drifts into the harbour of a small fishing village, it becomes a volatile catalyst for events that will ultimately tip the balance of political power, triggering a war that will end an era and usher in a new one.

Fortunately, the village overseer is Omi (Hiroto Kanai), an ambitious young lord who recognises the potential represented by this foreign vessel and its crew. He takes them prisoner and summons his samurai uncle, Yabushige (Tadanobu Asano), who’s only too happy to take possession of the Erasmus’s muskets and cannons. However, it seems my earlier statement of good fortune requires clarification. Not all the crew are so lucky, as one unfortunate soul is slowly boiled alive by Yabushige to assess how these strange foreigners face certain death.

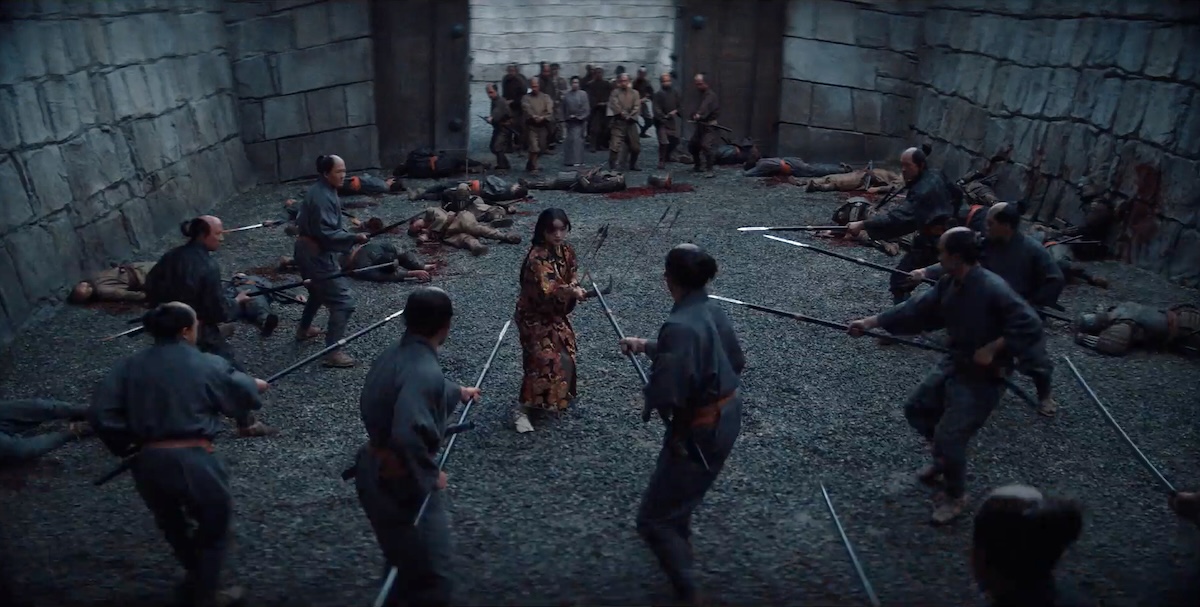

Visually, Shōgun can’t help but take its cues from Akira Kurosawa’s revered epics Kagemusha (1980) and Ran (1985), and Kinji Fukasaku’s equally stunning The Fall of Akō Castle (1978). This is particularly evident in its use of clean, minimalist interiors and the placement of players within them. The event in the pine room early in the first episode echoes events that also transpired in a room adorned with a pine motif, mirroring the trail of vengeance retold countless times in the famous tale of the 47 Ronin.

Here, it’s an equally pivotal moment as we are introduced to the Council of Regents. They have shared power over the nation since the death of the last Kampaku, a person of such high political rank that they could make decisions on behalf of the Emperor. Rather than risk civil unrest by appointing a direct successor until his heir comes of age, the power was shared among the warlords of the five main regions of Japan. It’s an uneasy alliance, with each regent vying to outmanoeuvre the others and gain supremacy, while still being bound by the strict samurai codes of conduct. At least to begin with.

They recognise that Lord Toranaga (Hiroyuki Sanada) of the Kantō region would’ve been the first choice as regent and so poses the greatest obstacle to their nefarious plans. Lord Ishido (Takehiro Hira) schemes to control or remove him, and has the support of the other regents. However, he is already having difficulties managing Lord Sadanaga of Higo (Hiromoto Ida) and the leprous Ohno Harunobu of Bungo (Takeshi Kurokawa), who’ve both converted to Catholicism and aligned themselves with the Portuguese Jesuits. Little do they know that they’re now pawns in a world-spanning power play, in which the Portuguese intend to assert their dominance by appointing Catholic rulers in their satellite territories, which they now believe include Japan.

When Toranaga learns of the arrival of a foreigner who declares himself an enemy of the Portuguese, he realises Blackthorne will be useful, although he doesn’t expect to eventually befriend him. Effectively under house arrest as a ‘guest’ at Osaka castle, Toranaga arranges for Blackthorne to be brought to him. He assigns Lady Toda Mariko (Anna Sawai) as a translator, distrusting the Jesuit priest Alvito (Tommy Bastow) and fearing his interpretation of Blackthorne’s words might not be entirely honest.

In a key scene of the second episode, “Servants of Two Masters”, Toranaga asks Blackthorne to draw a map of the world in the decorative, raked sand of his stone garden. Realising that honesty is his best chance of survival, Blackthorne explains that he’s English and his country is at war with the Spanish and Portuguese, who have divided the world into territories. He adds that these territories include secret bases manned by regiments of Japanese deserters. When he points out that Japan is under Portuguese control, Toranaga questions the translation. Mariko confirms that the word does indeed mean ‘to belong’. This is the moment that Toranaga grasps the significance of his situation and realises that the future of his country hangs in the balance.

It’s a simple scene of people talking in a garden, but it’s a fine example of how well-honed dialogue, finely nuanced performances, precise editing, and a supremely effective score all work together perfectly. The music is composed by Atticus and Leopold Ross, with some input from Nick Chuba. The Ross brothers have an impressive track record in alternative music and film scoring. Atticus is best known for his award-winning collaborations with Trent Reznor. I remember Leopold from his avant-garde pop-punk band Nojahoda, and I recently enjoyed his score for Apple TV’s Monarch: Legacy of Monsters, which also stars Anna Sawai.

Anna Sawai delivers a superbly subtle, repeatedly surprising performance as Lady Mariko, who, like all the other main characters, is based on a real historical figure. In this case, Lady Mariko is based on Lady Hosokawa Gracia, a Catholic convert and a key player in the Battle of Sekigahara. Her death triggered the events that brought the Sengoku period to an end, effectively establishing the Tokugawa shogunate and the relatively peaceful and politically stable Edo period. The story of Shōgun is as much hers as it is Blackthorne’s.

Lord Toranaga parallels the historical Tokugawa Ieyasu, who became the first shōgun of the Tokugawa shogunate. Hiroyuki Sanada matches Sawai’s subtlety, managing to convey so much through barely perceptible micro-expressions: a tilt of the head or a hand. Remarkably, he can communicate as much with a well-timed pause as he can with spoken words, sometimes even more. I remember Sanada for his supporting role in Kinji Fukasaku’s Samurai Reincarnation (1981), an excellent supernatural story that featured another version of Lady Hosokawa Gracia.

Cosmo Jarvis is anything but subtle, yet remains eminently watchable. He even manages to inject a good deal of humour into his performance, and is, understandably, in a permanent state of bewildered belligerence for the first few episodes. Because he’s ostensibly the protagonist, we feel we should identify with him, but we also find his bluster and bravado less appealing than the calm poise of the Japanese characters. This is part of the genius of James Clavell’s original story, in that it elicits a fascination for Japanese culture through its dramatised history.

“In 1600, an Englishman went to Japan and became a samurai.” James Clavell recounted that reading that simple statement in one of his daughter’s history books was the seed that grew into his bestselling novel Shōgun. He began researching the life and times of William Adams, the first and only foreigner to achieve the rank of samurai in feudal Japan—the inspiration for his fictional character, John Blackthorne. He would later sum up the story, saying, “It’s the story of a man who goes to Japan, becomes a samurai, and falls in love.” But did he mean in love with a woman, or in love with Japan?”

Clavell prioritised authenticity over historical accuracy in his novel. Therefore, he researched other real people and events from the same era, before remixing and repackaging them to serve his story. This tale follows an outsider thrust into feudal Japanese society, who must rapidly decipher their customs and conventions to survive. The author himself had a similar experience. At the age of 18, he was captured and held as a prisoner of war in Japan for three and a half years during World War II. The survival rate in the camp was one in fifteen, but he overcame his hatred, learned the language, and began to understand his captors and their vastly different cultural backgrounds. His debut novel in 1962, King Rat, dealt with this experience directly.

By then, he had already embarked on a successful screenwriting career, which included The Fly (1958). He’d also written and directed Five Gates to Hell (1959). He went on to write the classic prisoner of war film The Great Escape (1963) and directed several other films, including some based on his own scripts, such as To Sir, With Love (1967) and The Last Valley (1971). He also served as executive producer for the 1980 miniseries adaptation of Shōgun.

This new version is just as faithful to the original, overseen by its author more than 40 years ago. I can clearly remember several scenes that are closely replicated here. Who am I to judge how authentically feudal Japan is recreated on screen? I wasn’t there, and there are no eyewitnesses. All I can say is that it’s utterly convincing and, for the most part, beautiful.

The scrupulous performances from the high-calibre Japanese cast truly sell the authenticity. This, coupled with vast swathes of the language, is what makes the series so believable. Three ‘Masters of Gestures’ were employed as advisors for the cast. While the actors may be Japanese, they are modern people who might not be well-versed in the etiquette and customs of 17th-century Japan. Nevertheless, the series manages to immerse us so deeply in the aesthetic philosophies of that era that even a mud-and-blood-spattered samurai lifting a severed head on the rain-soaked battlefield possesses a strange sort of beauty. But this is mainly due to the cinematography, even though it’s heavily manipulated in post-production. The ubiquitous VFX are some of the most successful I’ve ever seen. Or rather, haven’t seen, because they’re so seamless that they go unnoticed.

Undoubtedly, the VFX are some of the best created for TV. Their scale rivals that of Game of Thrones (2011-19), but unlike the fictional world in that show, the recreation of the land here is thoroughly researched and digitally reconstructed. Long-lost castles are brought to life from historical prints and surviving architectural plans. The entirety of Osaka is a truly impressive vista, and the view we share with Blackthorn as his ship rounds a headland to enter its port is breathtaking. Even more memorable moments are yet to come.

The expansive, bird’s-eye-views used throughout as establishing shots are often incredibly believable – which isn’t a tautology. State-of-the-art VFX allows for the recreation of vast, historically accurate scenes, which would be impossible to film as these locations no longer exist. These CG sequences, impressive sets, and authentic locations all work together to transport us into a dreamlike vision of feudal Japan.

Most of these truly spectacular sequences come across as so real that viewers may only question them in hindsight. For instance, the earthquake scene was filmed using a real landscape digitally mapped at a super-high resolution and then animated. It’s better than reality in terms of visual storytelling clarity—more so than the equivalent scene in the ’80s production, where one of the special effects supervisors was buried alive during the full-scale practical effects of the earthquake! (Don’t worry, he survived.)

Despite around 6,000 special effects shots, Shōgun never feels like a technical showpiece. Some people in the background are avatars, the digitally scanned surfaces of actors wrapped around a CG model. This allows the 120 extras to be multiplied into armies of tens of thousands. Some of the objects the main characters interact with aren’t actually in their hands. Many of the swords and lances are virtual props. A sensible health and safety measure, to be sure. And if you’re squeamish, take some comfort that the copious blood in some scenes is just digital trickery added in post-production, which made set clean-up much easier.

The effects are always in service of the story, and the clarity of the storytelling is a major strength. I often find these epic sagas with multiple lords, houses, and fiefdoms difficult to follow. Perhaps I settled in so easily this time because I had seen the original 1980 miniseries and dipped into Clavell’s original novel some time ago, which inevitably has a more Westernised story structure. To generalise, Eurocentric and US storytelling stems from Greek myths and tends to adhere to a linear three-act, hero-led format. Asian stories are more often structured around four acts, are group-driven, and are less resolution-focused, acting as slices from bigger stories.

There seemed to be a time during my formative years when miniseries were a major part of the TV landscape. Long before they were known as ‘limited series’, they were major cultural events that everyone watched at the same time and would talk about all week as they waited for the next episode.

The late-1970s was the Golden Age of the television miniseries. The modestly produced I, Claudius (1976)—a dialogue-heavy, filmed play in 13 parts—had been a surprise hit. I recall fellow schoolchildren as well as my older relatives being eager to chat about it, but the following year truly set the bar for ‘limited series’ with Roots (1977). The streets were noticeably quieter when it was on, and it stands as one of the most-watched series ever, with over 100M viewers tuning in for its finale. It made it clear that programmes made for TV, when taken seriously, with high production values and a sufficient budget, could be as artistically and commercially successful as cinema.

The Word (1978) sticks in my mind as being the big one the following year, but it seems to have been largely forgotten now. Similarly, Quatermass (1979) only appealed to a more niche audience and never cracked the Top 20. However, it held the distinction of being the belated conclusion to the very first ever television miniseries: The Quatermass Experiment (1955), which was a massive hit with UK viewing figures averaging 3.9M. That might not sound impressive now, but back then the nation’s total audience was estimated at just 4M.

That era of the major miniseries culminated in two cultural phenomena in 1980 that seemingly everyone watched. These were Oppenheimer (1980) and Shōgun. So, clearly, the time has come to revisit these milestones in the TV landscape.

Roots had made its indelible mark on a budget of around $6.6M, but Shōgun upped the ante to an unprecedented $22M—which converts to around $70M in today’s money—bringing it in line with just a single episode of The Lord of the Rings: The Rings of Power. The 2024 remake of Shōgun reportedly cost around $250M, which was money well spent. That’s comparable to Marvel’s WandaVision (2021)—the show that brought the “blockbuster” miniseries back for modern audiences.

This new version of Shōgun, from showrunners Rachel Kondo and Justin Marks, surpasses the original in many ways and proved a hit with audiences, with its viewing figures steadily climbing. There’s already talk of a season two, but that seems unlikely, if not impossible. Clavell’s novel has been adapted. The story, of course, could continue, but the next book in his series, known as the ‘Asian Saga’, was Tai-Pan, published in 1966. Set in Hong Kong, it follows the territory falling under the influence of American and European factions following the Opium Wars—that’s more than two centuries after the events of Shōgun.

USA | 2024 | 10 EPISODES | 2.00:1 | COLOUR | JAPANESE • ENGLISH

writers: Rachel Kondo, Justin Marks, Shannon Goss, Nigel Williams, Emily Yoshida, Matt Lambert, Maegan Houang & Caillin Puente (based on the novel by James Clavell).

directors: Jonathan van Tulleken, Charlotte Brändström, Frederick E.O Toye, Hiromo Kamata, Takeshu Fukunaga & Emmanuel Osei-Kuffour.

starring: Hiroyuki Sanada, Cosmo Jarvis, Anna Sawai, Tadanobu Asano, Takehiro Hira, Tommy Bastow & Fumi Nikaido.