The Summer Film… and How it’s Changed

How blockbusters have evolved over the decades...

How blockbusters have evolved over the decades...

It’s now officially summertime. The sun is out. The beaches are fit to be swarmed, the campsites primed for barbecues. And when we’re not bronzing ourselves on the beach, or nestled deep inside a sleeping bag, perhaps we’ll decide to catch a film. But what’s showing?

Every year, there is a highly-touted summer movie to watch. However, what precisely is a summer movie? They are often spoken about as a predefined concept, a categorisation so obvious that it doesn’t require any further explanation. Nevertheless, properly examining what constitutes a summer film offers fascinating insights into traditional storytelling models, audience expectations, and the mood of the moment.

What makes a summer film summery? Is it the time of the year in which the film is released? Or is it related to the thematic underpinnings of the story? Maybe it is that the plot points evoke an aura of summer, or that our main characters exemplify attributes we would generally associate with the season. Perhaps, simplest, it’s a film set in locations that typify the summertime experience.

From my analysis, the summer movie encompasses one or all of these things, making it something of a fluid, ever-changing entity. The only real delineation I can confidently make between types of summer films involves a look at the storytelling intentions; is it plot-driven or character-driven? As you might argue, a good story is both. So, for the pedantic writers out there (a group in which I begrudgingly include myself), I will rephrase my observation: is the film high-concept or low-concept?

This may sound like the irritatingly simplified language of a Hollywood executive. However, when we use this model to analyse the intention of a story, it can often be illuminating, albeit occasionally reductionist. This tool is useful in determining how a narrative is likely to flow, but it’s by no means a panacea for storytelling.

A high-concept story involves a captivating, concise premise. It can be easily conveyed in a few words, ensuring the swift success of any elevator pitch. These stories generally feature a plot-driven approach to narrative. While characters don’t necessarily have to be lacking (and the film is massively improved if they aren’t), it’s understood that a fascinating plot is the primary attraction of these movies.

In stark contrast, a low-concept story is all about character. There probably won’t be a gripping hook or a premise that leaps out on the page. These stories usually have a more realistic depiction of life as they focus on an individual’s emotional and psychological development. As our protagonist faces obstacles throughout the narrative, we are less concerned with the plot than we are with the implications it has for our main character.

How do I know if the summer movie I’m picking up is a high-concept or low-concept film? Does it even matter? Well, that all depends on whether you prefer to watch romanticized adventures or adventurous romances. Do you want to watch a hero—or group of heroes—venture off with a pre-established goal, bathed in the golden hues of summer sunlight? Do you want to watch our protagonist solve a clearly defined problem, all while set in a beautiful touristy location? If the answer to either of these two questions is a resounding “yes,” then you’re most likely geared towards the romanticized adventure.

The romanticized adventure summer movie is pretty much exactly what it says on the tin. The adventures in these films aren’t especially arduous or demanding, and even more rarely are they emotionally draining. If they are any of these things, it’s usually a blip in an otherwise cohesive tale of fun, exhilaration, and discovery. These are glamorized depictions of leaving home, venturing into the unknown, and fulfilling a rather archetypal hero’s journey.

Think of the original Indiana Jones trilogy (1981-89), which were all released over the holiday period. I should mention now that, for the sake of my argument, I’m including May as part of summer. The reason why is that it’s abundantly clear Hollywood releases summery blockbusters in this month to capitalize on the public’s desire to be finished with spring and out lounging on deckchairs by the beach.

In other words, summer films, filled with adventure, danger, and mystery, are released in May to precipitate the season’s arrival. Both Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom (1984) and Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (1989) are set in faraway places, featuring a palpable summer atmosphere, though both were released at the end of spring. Part of this franchise’s immediate success is arguably due to the fantastic combination of the film’s tone and the distribution date: audiences flock to see the romanticised adventure in May to imagine what they could get up to in June.

Examples of this phenomenon can be found throughout film history (though mostly after the 1970s, which is when the blockbuster first gained credence as an entity). Star Wars (25 May 1977) became the most successful film ever made, partly because kids could see this exciting adventure film as many times as they wanted since school was finishing up. Alien (25 May 1979), released on the same day two years apart, ensured those same kids could experience their first taste of cosmic horror now that they were 730 days older.

Other classic examples of romanticised adventures include E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial (1982), Aliens (1986), Jurassic Park (1993), Independence Day (1996), Armageddon (1998), and Mamma Mia! (2008), all of which were released in July except for E.T. and Jurassic Park, which were both released in June. It would seem Steven Spielberg has a thing for that month…

It’s no coincidence that some of these films became some of, if not the highest-grossing pictures ever made. Star Wars, E.T., and Jurassic Park all topped this list at one point, each surpassing the other to claim the crown as Box Office King. Independence Day, meanwhile, became the second-highest-grossing film ever made in 1996. Needless to say, summer is the prime time to release a blockbuster.

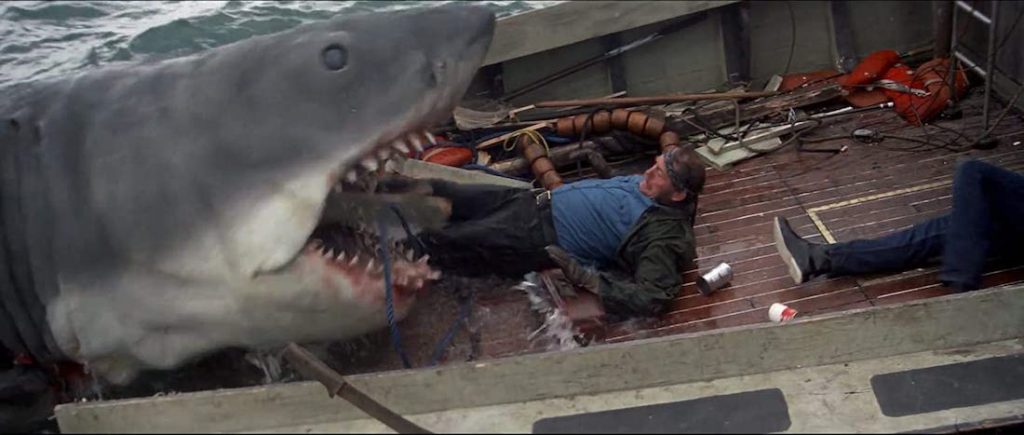

With this in mind, it’s worth mentioning that Spielberg is recognised as the undisputed champion of the romanticized summer adventure movie. Besides the aforementioned Indiana Jones films and his box-office-dominating films about aliens and dinosaurs, his first major work is widely considered the very first blockbuster ever made: Jaws (1975).

Released in June, Jaws is the quintessential example of a romanticized adventure. It’s a high-concept story: a giant shark terrorizes the small island of Amity, and three men set out to stop it. There’s the thrill of adventure and the fear of impending doom. The first barrel sequence epitomizes everything there is to love about the summer film: as an ominous and pervasive threat approaches, our heroes attempt to overcome it with cunning and derring-do. The story is set at the height of summer—which even inserts itself as an issue in the film—and mostly takes place on boats or beaches. What’s more summery than that?

However, if that’s not your style, then perhaps you’d prefer a quieter, more introspective story. Do you want to watch characters meet new people, with an air of mystery about whether these will be lasting relationships or catastrophic pairings? Or perhaps you’d like to witness our main characters engage in the carefree, reckless dalliances of youth, discovering they’ve fallen in love along the way?

If you’ve answered “yes” to either of these questions, then it sounds like you’re leaning towards the adventurous romance, the low-concept summer film. These stories are often populated by teenagers experiencing a slice of adventure in their personal lives: either through a new friendship, an intense personal experience, or a hero’s journey in miniature, these films often serve as stellar coming-of-age tales. Think Stand by Me (1986), Do the Right Thing (1989), Little Miss Sunshine (2006), or Dazed and Confused (1993). All summer-themed, all released during the summer.

The fiery romance, however, is arguably the most popular of these low-concept stories. After all, it’s the season most commonly associated with sex and romance; it makes sense that the films set during this period have a similar theme. However, given that our characters are often on the younger side, grappling with the formative years of their lives, these are frequently turbulent affairs. These romances are characterised by intense emotional conflict and personal hardship—young love, as they say.

Films featuring these tumultuous summer romances include: Eric Rohmer’s Claire’s Knee (1970), American Graffiti (1973), Grease (1978), Wet Hot American Summer (2001), Goodbye First Love (2011), and Call Me By Your Name (2017). While all were released during the summer months, Claire’s Knee and Call Me By Your Name are the exceptions, having been released in winter despite their sunny beach settings.

However, my choice for the quintessential summer romance would likely be A Summer’s Tale (1996). Another Eric Rohmer film, it was released in mid-July, the peak of summer. It’s a low-concept film with practically no plot. Our protagonist awaits his girlfriend’s arrival at a French beach, as arranged. When she doesn’t arrive, he spends much of the film waiting, encountering other young women who pique his interest.

The film revolves almost entirely around fleeting summer romances. Our unsure protagonist gains self-understanding through these encounters with contrasting women. Learning more about another person allows young lovers to experience more of themselves than they could have ever known; the closer our protagonist comes to another, the more intimately they begin to understand their own psychology.

This is a prevalent theme in the adventurous romance, especially when in a summer movie. In the criminally underseen Ava (2017), a young girl discovers that she will soon become blind, forging a powerful bond with a societal outcast. Beast (2017), another stellar film about romantic love between outsiders released the same year, features stormy beaches and mountainous landscapes which symbolise the adventurous nature of the romance on display. In stark contrast to the first category, these stories are very often arduous, demanding, and emotionally draining. As it’s the adolescent experience being documented, this only feels natural.

Having said all of this, there is a little bit of overlap in these stories. For example, one could make the argument that Mamma Mia! is more of a low-concept movie, one that features an adventurous romance. Though, I’d disagree: “A young girl invites three men to her wedding to discover which one is her father.” This has ‘elevator pitch’ written all over it. Though it all takes place in one location, the adventure comes to our protagonist, landing at a gorgeous summer hotspot in the form of three middle-aged men. Along the way, we discover who our protagonist’s father is and who desperately needs singing lessons.

However, in recent years, the lines between these two categories have shown greater signs of blurring. If we were to look at the two summer movies of last year, we can see that the borders have begun to merge, perhaps foreshadowed by the fact the two films were combined into an amusing portmanteau: ‘Barbenheimer’. This raises the question: are summer films changing?

Barbie (2023) was a high-concept blockbuster: “Barbie escapes Barbieland and discovers the world isn’t how she knows it to be…” That’s an elevator pitch. Oppenheimer (2023), in contrast, was low-concept: “Oppenheimer is tasked with designing the atomic bomb, although he has reservations about the ethical implications of his endeavour. Meanwhile, his loyalty to his country is tested when he’s accused of being a communist… And relationship troubles emerge…” I could go on. By the time you’ve described the plot or why Nolan’s latest outing is a must-watch, you’d have ridden that lift up and down five times.

A great summer film could always do a bit of both. There isn’t even a hint of adventure in A Summer’s Tale, though Ava features something akin to a summer escapade. Meanwhile, Jaws has impeccable character development and a subtle moral—but as previously mentioned, this doesn’t mean it’s low-concept. It simply augments the film overall, bolstering a high-concept plot with plausible, compelling growth in our protagonists.

Perhaps, the marketing of Barbie and Oppenheimer as a single entity suggests the potential for a thematic crossover. Just like Barbie, we’re being offered the best of both worlds. Or is that Hannah Montana?

Perhaps the most noticeable aspect of these two films is that neither feels particularly summery, despite being touted as summer blockbusters. While nobody expected Christopher Nolan’s masterpiece to be a jolly affair, even Barbie surprised audiences with its melancholic tone. This suggests a trend—summer films, regardless of high-concept or low-concept narratives, are becoming darker.

This has been evident since the early 2000s. Compared to Nolan’s summer blockbuster The Dark Knight (2008), Jaws feels like a joyous lakeside romp. Looking back at last summer and ahead to this season, both high-concept blockbusters and low-concept coming-of-age tales seem to be getting a touch gloomier. Furiosa: A Mad Max Saga (2024) is as gripping as it is grim, while The Bikeriders (2024) appears to be a brooding character study.

Is this a reflection of our existential anxieties surrounding summer in the face of climate change? Or perhaps an arbitrary shift in the zeitgeist? Director Ivan Reitman lamented the fact that the fun-loving spirit of 1980s comedies had been replaced by a desire for darker narratives within just five years. He cites this as a reason why Ghostbusters (1984), once the biggest comedy of all time, didn’t have a successful sequel: Ghostbusters II (1989) received a lukewarm box-office reception.

Are contemporary summer films reflecting this shift in social attitudes? This raises another question: do we tell the films how we’re feeling, or is it the other way around? Whatever the answer may be, it’s a question too large to answer here; it requires a more substantial piece of writing. To paraphrase Brody (Roy Schneider) in Jaws: “You’re gonna need a bigger essay.”